As a massage therapist, the most common complaint I hear on my treatment table is, without a doubt, that persistent, frustrating lower back pain. However, after a client finishes recounting their long days of sitting in an office or their regular running habits, my hands usually don't go directly to their back. Instead, they move to the front of their hips.At this moment, a look of surprise always appears on their face. But it is precisely in this often-overlooked corner that we find the real culprit: a group of muscles that are overused, yet chronically neglected—the hip flexors.

Among these, the main "hidden mastermind" is the iliopsoas, a muscle located deep within your core. It has a far greater influence on our posture, mobility, and even our perception of pain than you can imagine. Many people come to me with lower back pain, hip tightness, or difficulty walking, yet never thought that the root of the problem could come from the very front of their body.This article will be your personal guide. From a therapist's perspective, I will lead you to a deeper understanding of why your hips become tight, how to perform a self-assessment, and I will teach you how to safely release this tension to build a truly balanced and pain-free body.

Meet the Hidden Mastermind: Your Core Stabilizing Muscles

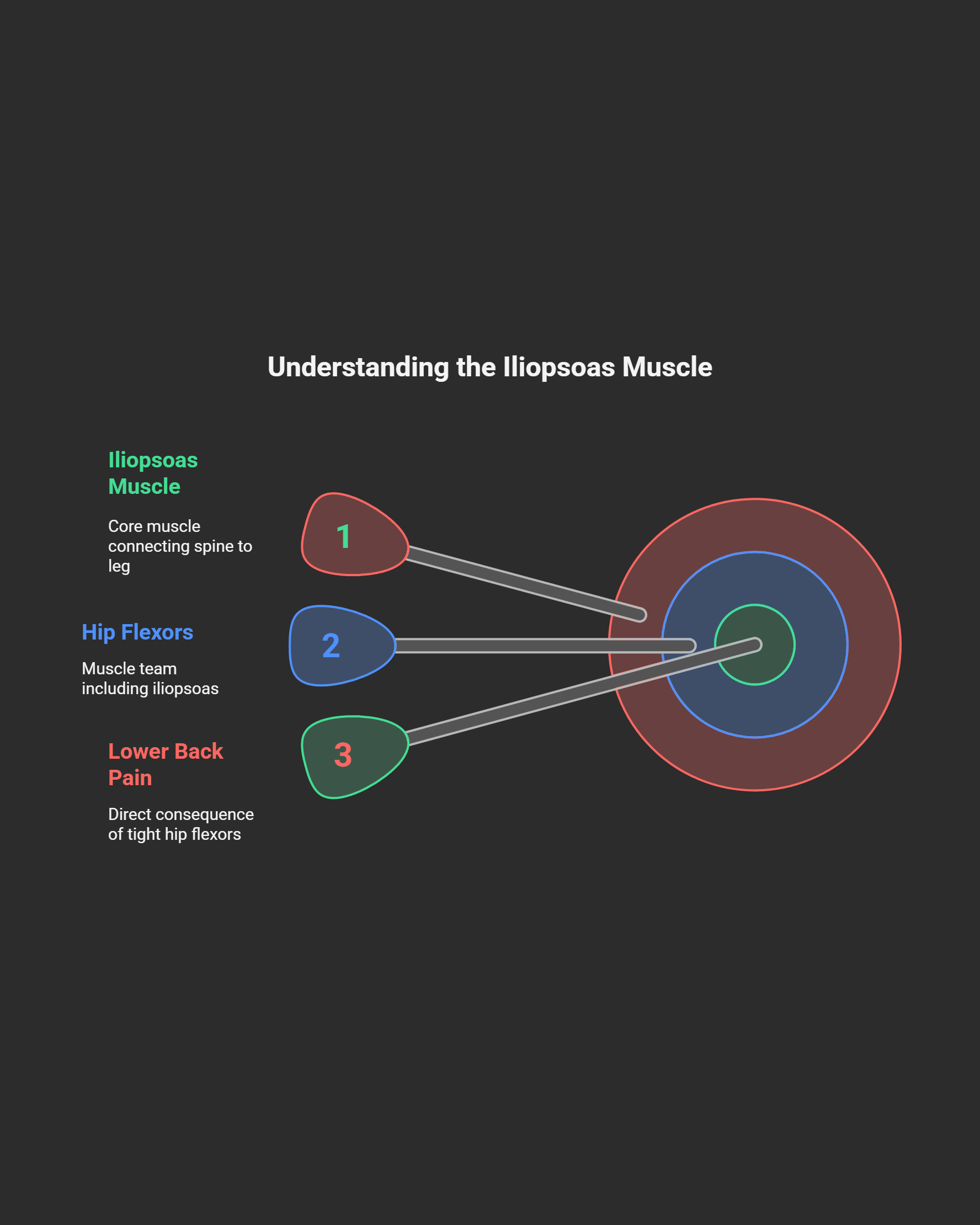

To solve a problem completely, we must first get to know it. The so-called "hip flexors" are not a single muscle, but a team that works in synergy, and the most important player on this team is the iliopsoas.This muscle is extremely unique. It originates from the vertebrae in your lower back, travels down through the deep abdominal cavity, and finally attaches to your thigh bone (femur). Remember this key fact: the iliopsoas is the only muscle that directly connects the spine to the leg. This direct anatomical link is the core to understanding why tight hip flexors directly cause lower back pain. It acts like a tightened cable, continuously pulling your lumbar spine forward.

In addition to the iliopsoas, which plays a major role, other supporting muscles assist in completing hip flexion, such as the rectus femoris on the front of the thigh and the tensor fasciae latae (TFL) on the outer hip.From a therapist's point of view, when I am treating a client, I can easily palpate the iliacus muscle on the inside of the pelvis, but accessing the deeper psoas major requires professional skill. It is precisely because of this deep muscle's direct connection to the lumbar spine that when it becomes tight due to lifestyle habits, so-called "lower back pain" is no longer a vague symptom, but a direct reflection of the health of your hip flexors.

The Cage of Modern Life: Why Are Your Hip Flexors Constantly Sounding the Alarm?

In modern society, our bodies are quietly adapting to a highly unnatural lifestyle, and tight hip flexors are a classic symptom of this maladaptation.When we sit for extended periods, our hip joints are held in a flexed position, which keeps the hip flexor muscle group in a constantly shortened state. To improve efficiency, the body initiates a mechanism known as "adaptive shortening," which, on a microscopic level, actually reduces the length of the muscle fibers.This isn't just a "feeling" of tightness; it is a change in the physical structure, much like a spring that can no longer fully extend after being compressed for a long time.

Interestingly, while a lack of activity is a primary cause, individuals who exercise regularly also face challenges. For athletes like runners and cyclists, whose sports require repetitive hip flexion, the hip flexor group can accumulate micro-trauma and chronic tension from the constant contraction. This is known as "Iliopsoas Syndrome."Whether it's from "not moving" or "moving too much," the result can be an imbalance in this key muscle group. Therefore, understanding the potential risks within your own lifestyle is the first step toward improvement, allowing us to address the specific cause rather than blindly treating the pain.

The Imbalanced Domino Effect: Lower Crossed Syndrome

Tight hip flexors rarely appear in isolation; they are often the core of a larger pattern of imbalance known as "Lower Crossed Syndrome."You can imagine drawing an "X" around the pelvic area: on one line are the tight and overactive muscles, including the hip flexors and the erector spinae of the lower back. On the other line are the weak and inhibited muscles, which include the abdominal core and the gluteal muscles.This imbalance acts like a tug-of-war, pulling the top of the pelvis forward and down, leading to a posture of anterior pelvic tilt. Visually, this often looks like a "perky butt" or a "Donald Duck butt."

Many people mistake this for a sign of being fit and athletic, but from a biomechanical perspective, it is actually a warning sign of dysfunction. An anterior pelvic tilt significantly increases the compression and shear forces on the lumbar spine joints. Over time, this can lead to joint wear-and-tear, increased pressure on the intervertebral discs, and even trigger chronic pain.Therefore, we must redefine the problem: the lower back pain you feel (the symptom) often does not originate from the back itself, but from a pattern of muscle imbalance centered on tight hip flexors, driven by lifestyle habits such as prolonged sitting. The key to treatment lies in breaking this vicious cycle.

The Therapist's Assessment: Are You a Victim, Too?

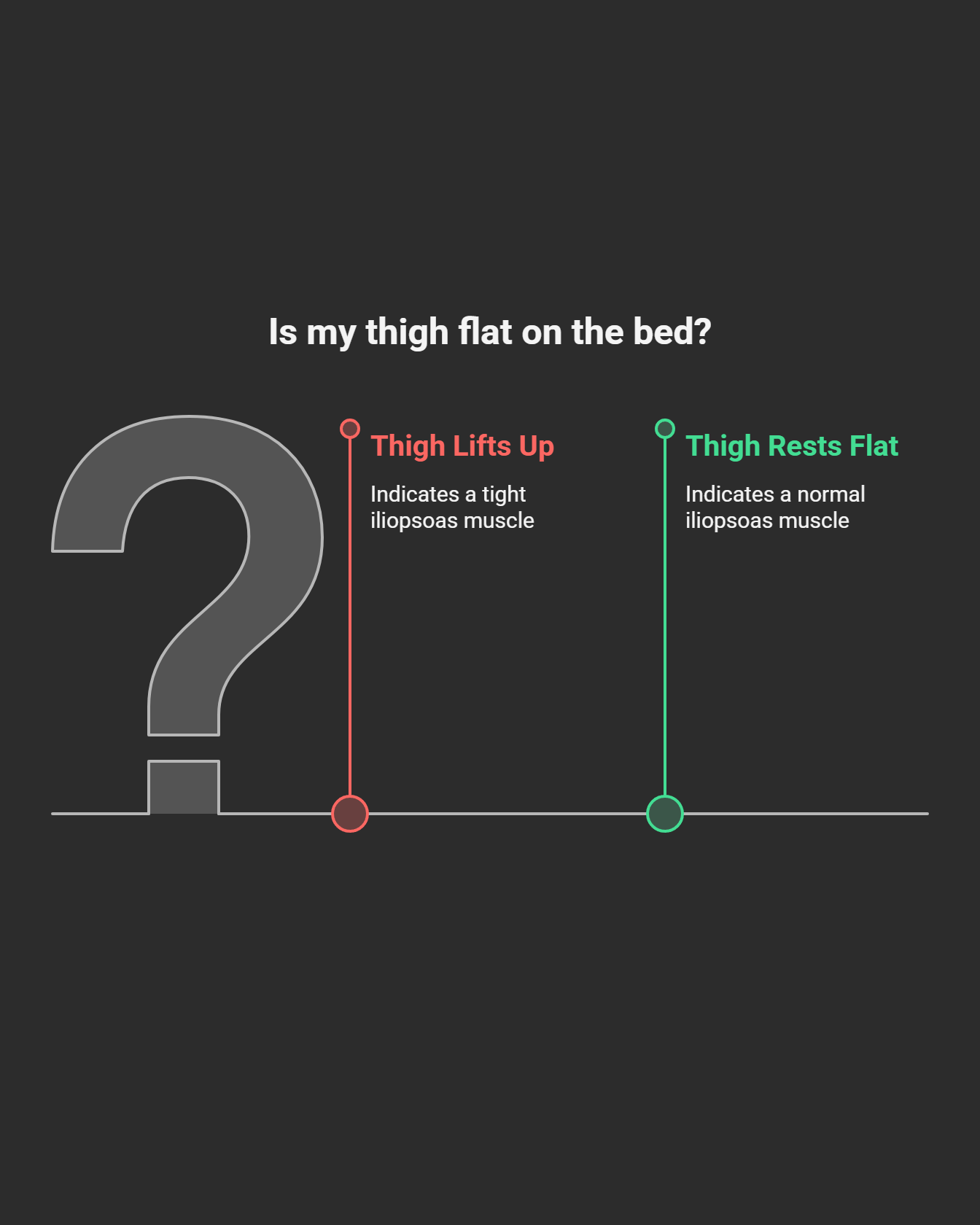

Before starting any stretching, performing a precise self-assessment is crucial. This allows you to transform from being a passive sufferer of pain into an active "body detective." The "Thomas Test" is a standard test frequently used by physical therapists to assess the length of the hip flexors, and you can perform it safely at home.Lie flat on the edge of a sturdy bed, allowing both legs to hang down naturally from the knees. Next, use both hands to hug the knee of one leg and gently pull it towards your chest. The key to this movement is to ensure that your lower back remains completely flat against the bed surface and does not arch.

While maintaining the knee-to-chest position, observe the other leg that is hanging down naturally. Under normal circumstances, the thigh of the extended leg should be able to rest completely flat on the bed.If the thigh of your extended leg cannot rest flat and lifts up off the surface, this usually indicates that your iliopsoas muscle is tight. If your thigh can rest flat, but your lower leg does not hang straight down and instead extends forward, this may indicate that the rectus femoris muscle (part of the quadriceps) on the front of your thigh is too tight. This simple test provides objective clues to help you confirm where the problem lies.

The Cornerstone of Relief: Mastering the Perfect Kneeling Stretch

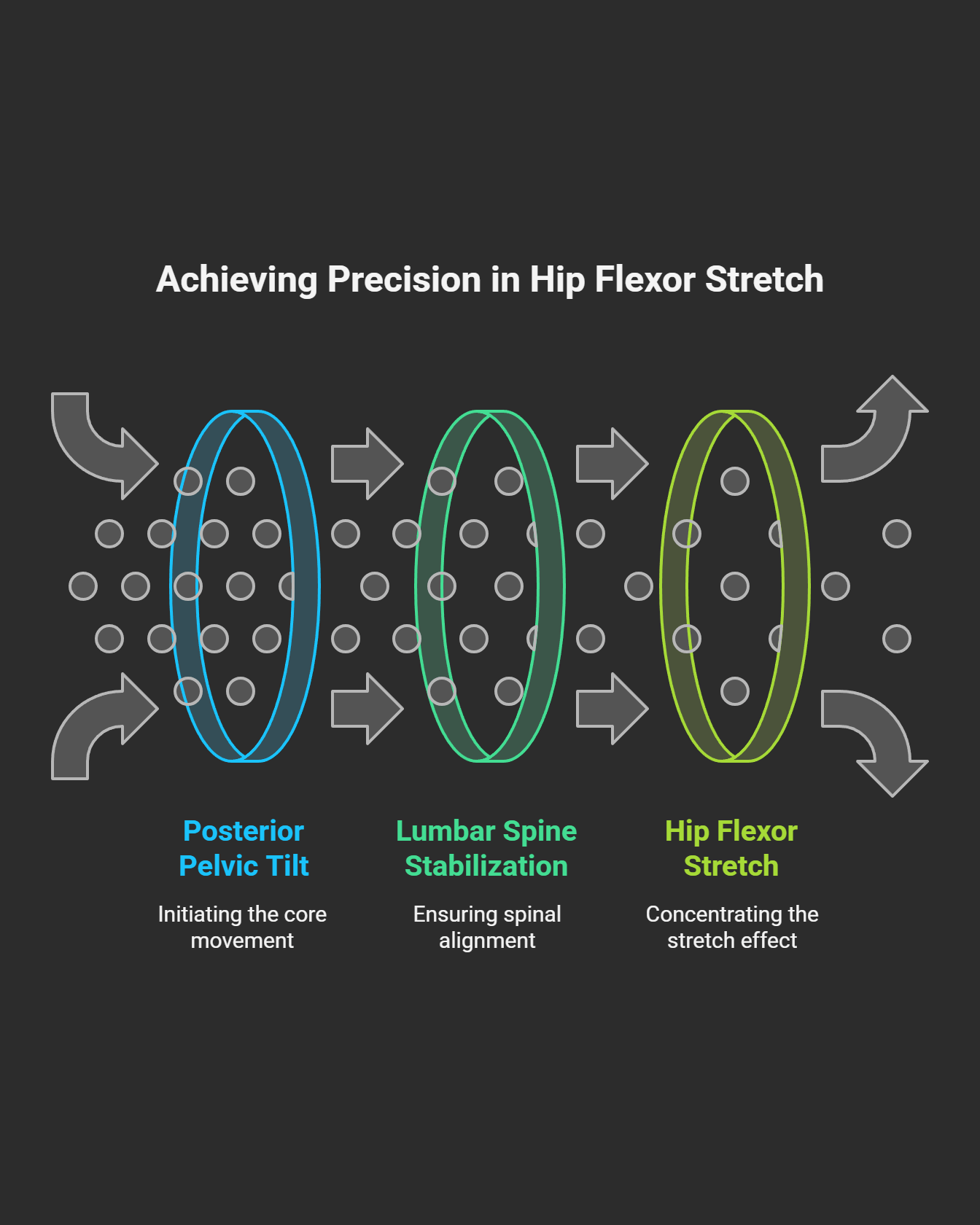

Among all hip flexor stretches, the kneeling stretch is the undisputed king because, when done correctly, it allows you to achieve the stretching effect with precision.First, assume a half-kneeling position with your front knee bent at a 90-degree angle, ensuring the knee is directly above the ankle. Before making any other movement, perform the most critical step: a posterior pelvic tilt. You can imagine this as "tucking your tailbone forward" or "gently squeezing the glute of your rear leg."This movement is the very soul of the entire stretch. It locks and stabilizes your lumbar spine, ensuring that the stretching force is concentrated on the hip flexors.

While maintaining the posterior pelvic tilt for the entire duration, shift your entire body's center of gravity forward very slightly. Remember, the range of movement is extremely small; your goal is to "feel the stretch," not to "cover distance."You should feel a clear stretching sensation deep in the front of your rear thigh, not a sense of compression in your lower back. Hold this position for 30 to 60 seconds, coordinating with deep, steady breathing. The most common mistake people make is to simply arch their back forward. This is not only ineffective but can also harm the lumbar spine, so be sure to avoid it.

More Than Just Stretching: Why You Must Also Strengthen

This is the one step most people overlook, and it's the fundamental reason why many complain that "the effects of stretching don't last."There is a principle in our nervous system called "reciprocal inhibition": when one muscle (like the hip flexors) is chronically tight and contracted, it constantly sends "relax, switch off" signals to its opposing muscle (the gluteal muscles). This is why people with tight hips usually also have weak and inactive glutes, leading to a condition known as "gluteal amnesia."You can stretch your hip flexors all day, but if you don't wake up and strengthen the "amnesic" glutes and your core, the pattern of imbalance will always remain.

Therefore, strengthening is the other half of the equation. I strongly recommend incorporating two foundational exercises:The "Glute Bridge" directly awakens and trains the gluteus maximus, which is the primary force to counteract tight hip flexors. The "Dead Bug" trains the deep core's ability to stabilize the pelvis, directly working against an anterior pelvic tilt. The recommended sequence is to "stretch first, then strengthen." First, restore the muscle's correct length through stretching, and then use strength training to solidify this new, more balanced body posture, making the results more lasting.

Conclusion: The Sustainable Path to Hip Health and a Pain-Free Back

Liberating your body from the "cage" of modern life is a journey, not a destination. It requires patience, consistency, and listening to your body's signals.Please remember this core maxim: Assess, Release, Stretch, and Strengthen.This is a complete solution: first, assess your body to identify the problem. Next, you can release by using a foam roller or massage ball for self-myofascial release. Then, perform precision stretching to restore muscle length. Finally, you build long-term stability by strengthening the weak muscle groups.

I suggest you can arrange your routine as follows:Daily: Spend 5-10 minutes, especially after long periods of sitting, performing 1-2 sets of the kneeling hip flexor stretch and the glute bridge. Weekly: Three times a week, perform a more complete 20-minute maintenance session, combining myofascial release, a variety of stretches, and core and glute strengthening. Of course, if the pain is very severe, is accompanied by numbness, or does not improve after several weeks of self-care, please be sure to consult a qualified therapist or physician.By understanding the "why" behind your pain, what you are doing is not just stretching—you are paving a path for yourself toward a more flexible, stronger, and pain-free life.